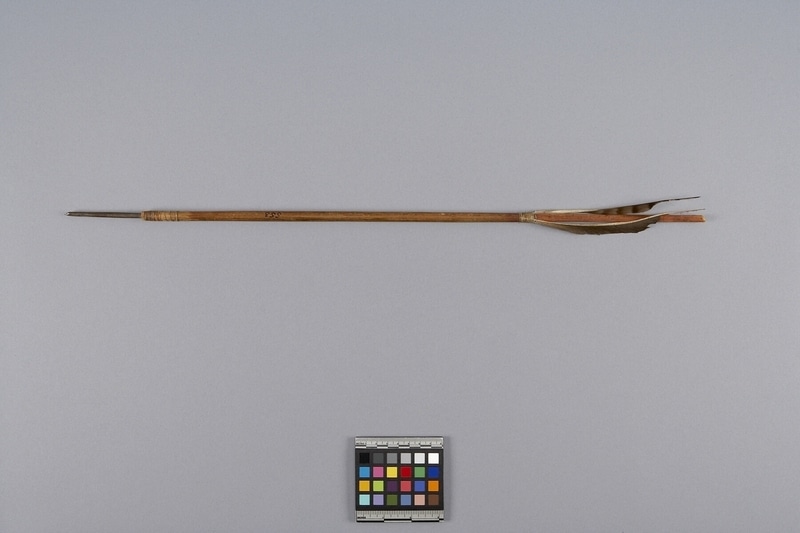

Arrow Item Number: Nb662 from the MOA: University of British Columbia

Description

Arrow with long cylindrical wooden shaft with one end notched and broken. The other end has a metal point that is secured with wrapped sinew. The metal point is round at shaft end, but the pointed end has been flattened and cut. The opposite end of the shaft is stained with red pigment, possibly ochre, and has 2 strips of feather secured with sinew.

History Of Use

The bow was used as the primary weapon for hunting land animals. Arrows were specialized for hunting animals or birds. Arrows used for bird hunting had "a hardwood knob or a fiber wrapping at the end of the shaft (Barnett 1955:102)." While a very common shape for other types of arrows was a " point [that] was five or six inches long. Both for hunting and warfare, it was set into a slot in the blunt, untapered end of the shaft in such a way that, when the victim was pierced, the shaft dropped off and the point remained in the wound (1955:102)." Wilson Duff reports that arrows of bone and ground stone were used by the Sto:lo for hunting, while those of chipped stone were used for war. He adds that the war point were sometimes poisoned by dipping them in the human brain (see 1952:59).

Cultural Context

hunting; warfare

Narrative

This arrow was found in a shell heap near New Westminster, with four others, between 1920-1927. Frank Burnett, the collector, sailed around British Columbia during this period collecting artifacts.

Specific Techniques

Wilson Duff reported that the Sto:lo made arrows from serviceberry wood, and that "some persons used small round sprouts, but deer hunters used larger and tougher stems split into four and rounded. The point of the arrow was charred and sharpened, and this sufficed for a point in most cases. Sometimes, however, points were made of ground slate...[also] of bone, ground stone, and chipped stone... Arrows were feathered with the whole tail feathers of mallard ducks or woodpeckers. Two feathers were used, laid on tangentially opposite each other. The feather was laid on the arrow, quill-end toward the butt, and the end of the vane was tied to the arrow with deer sinew. The quill-end was brought forward and tied down forward of the previous lashing. Sometimes it was given a half-twist to impart a rotary motion to the arrow in flight" (from The Upper Stalo Indians. 1952:59).

Item History

- Made in British Columbia, Canada before 1927

- Collected in New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada between 1920 and 1927

- Owned by Frank Burnett before 1927

- Received from Frank Burnett (Donor) on July 25, 1927

What

Who

- Culture

- Coast Salish: Sto:lo: Kwantlen

- Previous Owner

- Frank Burnett

- Received from

- Frank Burnett (Donor)

Where

- Holding Institution

- MOA: University of British Columbia

- Made in

- British Columbia, Canada

- Collected in

- New Westminster, British Columbia, Canada

When

- Creation Date

- before 1927

- Collection Date

- between 1920 and 1927

- Ownership Date

- before 1927

- Acquisition Date

- on July 25, 1927

Other

- Condition

- good

- Current Location

- Case 7

- Accession Number

- 2191/0220